Why Mearsheimer is wrong on China

I know many people are puzzled by Mearsheimer's apparent inconsistency between his positions on Russia and on China.

He has long argued that NATO expansion was a major mistake that would provoke Russia and start a war in Ukraine, yet he simultaneously argues in favor of similar actions in Asia to "contain" China. Why be so careful about not provoking one whilst actively seeking to provoke the other? All the more when China is vastly more powerful than Russia and doesn't have the history of military interventions that Russia does.

To be fair to him, he acknowledges that there's a form of double standard in his position. In his words: “Several people – including Mr. Bertrand [that’s me!] – have been struck by the fact that I think differently about US policy toward Ukraine/Russia than Taiwan/China.”

In a message to me back in December 2022, he laid out his thinking on this matter:

First, China is a peer competitor of the US and is a threat to establish regional hegemony in Asia, which is not in the American national interest. Therefore, China must be contained, and Taiwan is a key element in a sound US containment strategy.

Russia, on the other hand, is a weak great power and no threat to dominate Europe. It is much less powerful than the Soviet Union or contemporary China. Thus, I believe that the US does not even have to be in Europe today to counter Russia, much less pushing to expand NATO eastward to include Ukraine. Second, even if the US faced a very powerful Russia that needed to be contained, it would be foolish to move to incorporate Ukraine into NATO. The reason is simple: it would involve the US and its allies marching eastward into Ukraine, which almost certainly would precipitate a great-power war that might escalate to the nuclear level. Such behavior is hardly consistent with a smart containment strategy.

The situation regarding Taiwan is fundamentally different. The US is already firmly ensconced in East Asia and has a rich history of close military (as well as economic & political) ties with Taiwan. In other words, the US does not have to move westward into China’s backyard to establish military ties with Taiwan, which would likely precipitate a great-power war. None of this is to deny that the situation today involving Taiwan is dangerous and needs to be carefully managed to avoid a Sino-American war that runs the risk of turning nuclear.

Basically his position stems from his "offensive realism" theory that posits that great powers are inherently driven to maximize their power and seek regional hegemony.

At heart he thinks that by far the greatest "threat" to US power is China, not Russia, because China is “a peer competitor of the US and is a threat to establish regional hegemony in Asia, which is not in the American national interest.” As such, or so goes his theory, the US must prioritize containing China's rise over all other considerations, including the risk of military confrontation that he deems unacceptable when it comes to Russia.

In short, his view is that the US should focus its containment efforts on genuine peer competitors while avoiding unnecessary provocations of weaker states that pose no fundamental challenge to the US.

Sounds reasonable? At first glance, you could say so: in theory, it makes strategic sense to allocate your limited resources toward countering your most capable rival while avoiding costly distractions with lesser powers.

Yet, when one digs into his position in a bit more details, there are actually a number of incoherencies and contradictions that make his approach both theoretically incoherent and practically dangerous.

Here are the 4 key arguments that expose the flaws in Mearsheimer’s reasoning on China.

Argument 1: He promotes what he condemns

The most interesting contradiction in Mearsheimer’s views is that he is simultaneously one of the fiercest critics of U.S. behavior on the world stage, with so little of it that he finds redeemable, yet at the heart of his China policy is a demand that America double down on the imperial overreach he so consistently and eloquently diagnoses as the source of its greatest disasters.

Ukraine is a case in point. For more than a decade Mearsheimer has warned that NATO expansion eastward would provoke Russia into a devastating war, arguing that American policymakers were recklessly ignoring geopolitical realities in pursuit of idealistic goals. He predicted with remarkable accuracy that this policy would lead to catastrophe, condemning it as a textbook example of how American hubris creates the very conflicts it claims to prevent.

Or take Gaza. Mearsheimer, the man who literally wrote the book on the Israel lobby, has not hesitated to call what the US and Israel are doing in Gaza a genocide, arguing that American complicity in such actions represents the moral bankruptcy of a foreign policy driven by domestic lobbying rather than strategic wisdom or ethical considerations.

Or take the latest war on Iran. Mearsheimer has been equally scathing about the US-Israeli bombing campaign, arguing that Israel has a “deep seated interest in wrecking all of their neighbors” and seeks to “fracture them, break them apart” by being “joined at the hips with the United States” - with America only too happy to oblige due to the Israel lobby.

He further points out that the bombing campaign designed to destroy Iran's nuclear capabilities “has had exactly the opposite effect” of what was intended: “the hardliners have taken over, the revolutionary guards are in control more than they ever were.” Drawing on what he calls “a rich history of this happening every time a country launched a bombing campaign against another country for the purposes of regime change,” he dismisses the entire enterprise as strategically bankrupt, asking sarcastically whether anyone really believes a new Iranian regime would say “we don't want nuclear weapons, we don't want to cause Israel or the United States any trouble in the region and we're going to behave ourselves according to the dictates of Israel.”

Once again, his message is clear: American power, wielded recklessly and in service of foolish agendas, consistently produces disastrous outcomes.

So, given all this, how can he then simultaneously argue for maximizing the very American power he keeps documenting as the main source of global instability? The contradiction is stark: if US power produces such catastrophic results, why advocate for its preservation and expansion against China rather than its restraint and reform?

This is all the more contradictory when one considers that what China advocates on virtually all the issues that Mearsheimer comments on is remarkably aligned with Mearsheimer’s own views.

On Ukraine, China has consistently opposed NATO expansion and China's official news agency Xinhua even regularly publishes and praises none other than Mearsheimer himself on the matter, celebrating his warnings about Western overreach and his predictions about the conflict. On Gaza, China advocates for exactly what Mearsheimer calls for: an end to American enablement of Israeli overreach and support for Palestinian self-determination. And on Iran, China opposes precisely the kind of preemptive military action that Mearsheimer argues represents American strategic incompetence.

So it's the ultimate strategic paradox: advocating for the continued hegemony of a power he considers reckless and destructive over a rival that embodies the very restraint and realism he claims to champion.

I understand that Mearsheimer is American and naturally wants his own country to be more powerful than others, but this patriotic preference reveals a fundamental intellectual bias at play here. If his own analytical framework were to be applied consistently and if he were to look at it from the standpoint of a neutral observer seeking to minimize human suffering and strategic disasters, he would have to conclude that constraining the demonstrably war-prone reckless hegemon (America) while accommodating the rising but restrained power (China) is the truly realist path forward - regardless of which passport he holds.

Argument 2: For a realist, he’s not realistic

One counter-argument Mearsheimer could make on the above is that, as an academic, he isn’t in the business of advocacy but in the business of trying to understand and explain great powers’ behavior.

As such, he could say that he does not in fact want the US to contain China, he merely explains that America has no choice but to do so, since offensive realism dictates that dominant powers must prevent any rival from achieving regional hegemony.

I will set aside here the fact that if one actually listens to Mearsheimer, the language he uses to make his case is unmistakably that of advocacy, consistently blaming American policymakers for their “foolish” decision of not focusing on containing China. He calls engagement with China a “colossal strategic mistake” and repeatedly describes US policy as “foolishly” helping China become a rival power. He argues that “American policy toward China and American policy toward Russia have pushed them closely together” and describes fostering Chinese growth as “remarkably foolish.”

This is hardly the dispassionate language of a scholar merely describing inevitable structural forces, and this alone would in and of itself disprove any defense that he's simply explaining what must happen rather than arguing for what should happen - no truly descriptive theorist speaks of “mistakes” and “foolishness.”

But even setting this aside, there is one big - in fact a fundamental - problem with Mearsheimer’s argument that America will contain China’s rise: it just isn’t happening.

You can actually see it in his own discourse: the reason he calls American policymakers “foolish” is precisely because they are not doing what his theory predicts they ought to inevitably do - if containing China were that deterministic and truly structurally inevitable, there would be no “foolishness” to condemn.

And in fact there are growing signs that, far from containing China’s rise, the US are in fact in many ways withdrawing from Asia.

This presents a big blow to Mearsheimer's theoretical framework. If offensive realism's central prediction - that dominant powers inevitably prevent rivals from achieving regional hegemony - were correct, we should see America mobilizing overwhelming resources to maintain its position.

Instead, Hugh White, one of Australia's foremost strategic thinkers and the former Deputy Secretary for Strategy and Intelligence in the Australian Department of Defence, shows that it’s just not happening as I explained in a recent article. As White puts it:

What's happened is that as China's challenge has picked up, become more intense, The United States faced a choice. It could either push back decisively and really work hard to preserve America's position, or it could acquiesce in China's bid to push it out. Now what America has in fact done is talk about pushing back, and it's done so quite consistently. Barack Obama came in fact to Canberra where I'm speaking from to declare the pivot in 2011, talking about America being all in to preserve its position as a leading power in East Asia. He talked about using all the elements of American power.

And there was a kind of an interregnum under Trump, and then the Biden administration came back in and talked a lot about pushing back against China. Joe Biden talked about being in the contest for the 21st century, winning the contest for the 21st century against China.

But if you look at what America actually did, the answer is just about nothing.

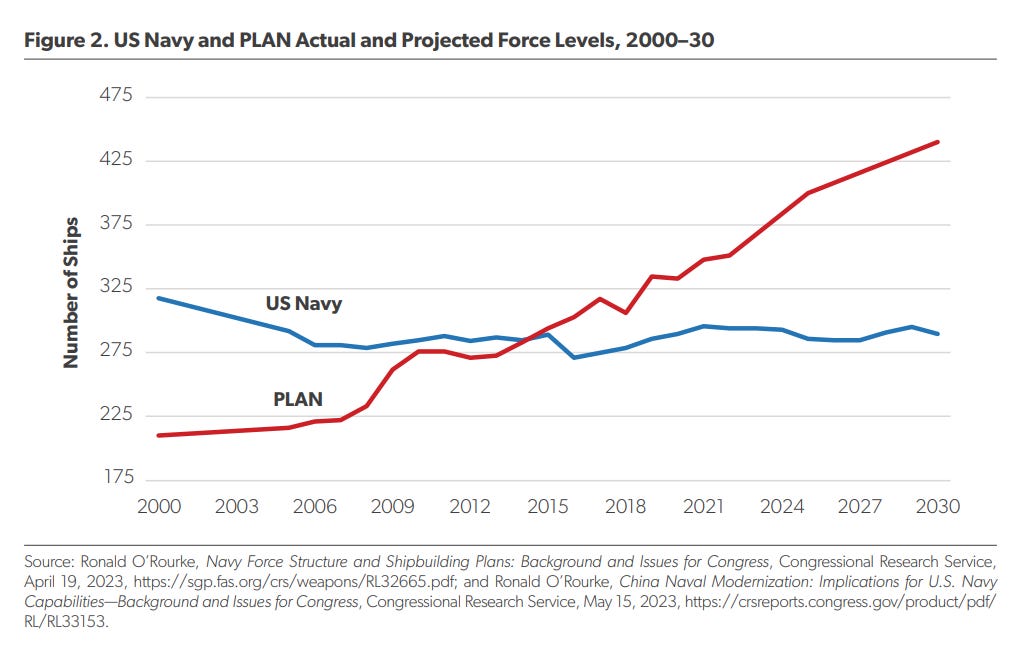

If you look simply at the military dimension, this graph is immensely telling:

As you can see, this graph provides devastating visual evidence of White's point. While America spent over a decade talking about “pivots” and being “all in” to preserve its position in East Asia, China's navy surpassed the US Navy in total ship count by 2015 and has continued growing relentlessly ever since. Meanwhile, the US Navy has remained essentially flat, even declining slightly. This isn't the behavior of a dominant power following Mearsheimer's structural logic - it's the behavior of a power that has already conceded the contest, and simply talks the talk without walking the walk.

A similar dynamic is happening when it comes to America's alliances in the region: for instance looking at Southeast Asia, despite decades of American rhetoric about 'pivots' and renewed commitment, systematic analysis reveals a region drifting steadily toward China. Scholars in Singapore tracking alignment patterns found that even as Washington talks about strengthening partnerships, at this stage there only remains a single country in the region that’s more aligned with America than China, the Philippines. And according to their analysis, even it has moved in China's direction. The remaining nine countries are either aligned with China or hedging while trending Chinese.

So the reality is this: instead of rallying allies against a rising challenger, America is presiding over their systematic defection. Reality ought to matter when it comes to realism, no?

To top it all off, we're now at a stage where containing China is entirely futile given the structural realities at play. This reveals the irony at the heart of Mearsheimer's work: for someone who is supposedly the ultimate “realist” in international relations, his analysis has become unrealistic - not just because his predicted containment behavior didn't occur, but because he continues to advocate for policies that are now structurally impossible to implement. White’s evidence shows that the window for containment closed over a decade ago, and that America now completely lacks both the economic mass and military capacity to reverse China's rise.

Conclusion: Mearsheimer's case represents a cautionary tale about the dangers of theoretical rigidity in the face of contradictory evidence. The patron saint of realism is Otto von Bismarck, who famously declared that politics is the art of the possible- that effective strategy must be grounded in what can actually be achieved rather than what theory suggests should happen. Yet Mearsheimer has done precisely the opposite - continuing to insist that America will inevitably contain China even as all available evidence points in the opposite direction, from naval balance charts showing China's fleet growth while America's stagnates, to systematic alignment indices revealing Southeast Asian countries drifting toward Beijing despite talks of American “pivots.”

A true Bismarckian would recognize that great powers can choose - consciously or through accumulated smaller decisions - to accommodate rather than confront rising challengers, and that in the present case America has already made its choice.

Argument 3: Why would this time be different?

An interesting irony with Mearsheimer is that every time he seems to accurately predict US behavior - and to be fair to him he’s repeatedly been very prescient - it is precisely when America does NOT act in ways championed by his “offensive realism” theories.

Ukraine is a case in point. Mearsheimer's remarkably accurate prediction that NATO expansion would provoke Russia into war stemmed from his understanding that America would do precisely the opposite of what his theory recommends. Rather than focusing containment efforts on the genuine peer competitor (China) while accommodating or even allying with the lesser power (Russia), the US would instead waste resources provoking Russia - exactly what Mearsheimer argued against.

Same thing when it comes to Gaza and the US's general behavior in the Middle-East over the past 20 years. Mearsheimer has continuously been immensely prescient about American strategic disasters precisely because he understands that the US will consistently do the opposite of what his theory recommends.

On the Iraq War, he co-authored articles in 2003 calling it an “unnecessary war” with no compelling strategic rationale, correctly predicting it would be a costly distraction.

On Gaza, he has been equally prescient about how American complicity in what he calls genocide would undermine US global credibility and hand victories to Russia and China.

The irony is somewhat hilarious: his most successful predictions come from understanding that America will systematically violate the very strategic logic he claims should govern great power behavior, getting bogged down in exactly the kind of self-harming peripheral conflicts that his theories say the US should avoid.

This all begs the question: if Mearsheimer's most accurate predictions stem from his understanding that America systematically ignores offensive realist logic, why does he suddenly expect the US to embrace that very logic when it comes to China?

His genuinely impressive track record of successful forecasting is built entirely on recognizing that America will do the strategically incoherent thing - waste resources on peripheral conflicts, provoke lesser powers while ignoring greater ones, and prioritize ideological commitments over strategic imperatives. Yet somehow, when it comes to the far more demanding challenge of containing a genuine peer competitor, he expects this same strategically dysfunctional country to suddenly develop the focus, commitment, and resource allocation discipline that it has not demonstrated in decades.

His own predictive success provides the best evidence against his China containment thesis.

Argument 4: If America doesn't act 'offensive realist', why would China?

Lastly, his theory is not only predicated on the US’s behavior but also on China’s: he argues that China is a “threat” because it will inevitably do what rising great powers do and seek hegemony at the expense of the United States.

But this prediction rests on the same flawed theoretical foundation that has consistently failed to explain American behavior. If Mearsheimer cannot accurately predict how his own country - with its culture, institutions, and strategic traditions that he knows intimately - will behave, why should we trust his ability to forecast the actions of China, a civilization with entirely different historical experiences, strategic culture, and decision-making processes?

In his fascinating book on the Thucydides Trap, Harvard scholar Graham Allison makes the point that when America itself was the rising power over a century ago, it behaved exactly as Mearsheimer's theory predicts rising powers should behave.

Under Theodore Roosevelt, the US was relentlessly expansionist, intervening militarily nine times in seven years, expelling European powers from the Western Hemisphere, manufacturing wars to acquire territory, and declaring itself the regional policeman with the right to intervene “whenever and wherever it judged necessary.” This was textbook offensive realism in action.

Yet China today - despite being in a similar position as a rising power challenging an established hegemon - has followed a completely different playbook, avoiding military interventions, seeking economic rather than territorial expansion, and showing none of the aggressive territorial acquisition that characterized America's rise. If Mearsheimer's theory were truly universal, we should see China behaving like Teddy Roosevelt's America. Instead, we see the opposite.

You can also look at China’s discourse. Despite all the verbal hostility coming from the US’s side, we’re seeing no Teddy Roosevelt-like calls by China to establish exclusive spheres of influence.

Where Roosevelt proclaimed that America would “drive every European power off of this continent,” Chinese leaders speak of building a “Community With a Shared Future for Mankind” based on the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, and of building a “New Type of Great Power Relations” where where both powers can prosper simultaneously by “abandoning the zero-sum game mentality and advancing areas of mutual interest.”

This inclusive vision stands in stark contrast to TR's exclusive hemispheric dominance. China's rhetoric emphasizes shared global governance, peaceful coexistence and cooperation - concepts that would have been foreign to the man who believed that “all the great masterful races have been fighting races.”

Deng Xiaoping himself, in a 1974 speech at the UN, said that “if one day China should change her color and turn into a superpower, she too should play the tyrant and everywhere subject others to her bullying, aggression and exploitation, the people of the world should identify her as social-imperialism, expose it, oppose it and work together with the Chinese people to overthrow it.”

As Zhao Long from the Shanghai Institute for International Studies explains, Western realist thinking operates on win-lose logic where great powers must dominate exclusive territories, while China's approach is fundamentally systemic, focused on maintaining stability within an interconnected global order. China sees itself not as a competing heart trying to dominate other organs, but as part of a global body where prosperity depends on healthy circulation throughout the entire system.

China's strength actually lies precisely in rejecting conventional great power competition. As Zhao Long notes: “Beijing's influence grows when its regional partners are economically linked to a wider global system in which China plays a central role - not when those partners are locked into rigid geopolitical blocs.”

This means that assuming that China will play the deterministic role of an aggressive rising power bent on regional hegemony misses the point entirely: it's not that China is hiding its true hegemonic ambitions, but that it believes hegemony would actually undermine the very global integration that China understands is the root of its prosperity.

It goes to show that here again Mearsheimer theories are deeply flawed: he mistakes the particular strategic culture and historical experience of rising Western powers for universal laws of international relations. His “offensive realism” may accurately describe how America and European powers have historically behaved, but it fundamentally fails when applied to civilizations with entirely different philosophical foundations about power, harmony, and interstate relations.

Lastly, if you’re not convinced, you can also look at China’s own history because, contrary to the US, this isn’t China’s first rodeo: it’s been the greatest power in its region for some 1,800 of the past 2,000 years. During this time, China had countless opportunities to behave like the aggressive, territorially-expansionist hegemon that Mearsheimer's theory predicts all dominant powers become. Instead, we see a pattern of behavior that prioritized stability, cultural influence, and economic relationships over territorial conquest and military domination. Incidentally not so different from the systemic, harmony-focused approach that Chinese leaders articulate today.

The end of the Western model?

Perhaps the most interesting insight that transpires from Mearsheimer's contradictions is that traditional methods of maintaining hegemony - military intervention, coercive diplomacy, alliance management through dominance - are producing diminishing returns and often backfiring entirely. All the failures he documents - from Ukraine to Gaza to broader Middle Eastern interventions - haven't just failed strategically; they've actively undermined American influence by delegitimizing American leadership in much of the world.

Meanwhile, China's rise appears to rest precisely on rejecting this model, building influence through economic integration and institutional development rather than military intervention. The beautiful irony is that it is precisely being restrained and not “offensively realist” that’s in many ways fueling China’s success.

As such, maybe the ultimate lesson from Mearsheimer's contradictions is that moral authority and strategic effectiveness are not opposing forces - they are the same. The ultimate irony may be that the world Mearsheimer appears to prefer - one where great powers exercise strategic restraint, avoid costly interventions, and focus on genuine security rather than imperial ambition - may arise not by following his offensive realist prescriptions, but in opposition to them.